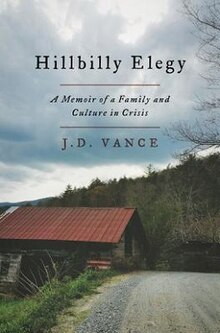

Hillbilly Elegy

| |

| Author | JD Vance |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Rural sociology, poverty, family drama |

| Published | June 2016 (Harper Press) |

| Publisher | Harper |

| Pages | 264 |

| Awards | 2017 Audie Award for Nonfiction |

| ISBN | 978-0-06-230054-6 |

| OCLC | 952097610 |

| LC Class | HD8073.V37 |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis is a 2016 memoir by JD Vance about the Appalachian values of his family from Kentucky and the socioeconomic problems of his hometown of Middletown, Ohio, where his mother's parents moved when they were young. It was adapted into the 2020 film Hillbilly Elegy, directed by Ron Howard and starring Glenn Close and Amy Adams.[1]

Summary

[edit]Vance describes his upbringing and family background while growing up in Middletown, Ohio, where his mother and her family had moved after World War II from Breathitt County, Kentucky.

Vance states that their Appalachian culture valued traits such as loyalty and love of country despite family violence and verbal abuse. Vance recounts his grandparents' alcoholism as well as his mother's history of drug addictions and failed relationships. Vance's grandparents reconciled and became his guardians. His strict but loving grandmother pushed Vance, who went on to complete undergraduate studies at Ohio State University and earned a Juris Doctor degree from Yale Law School.[2]

In his personal history, Vance raises questions about the responsibility of his family and local people for their misfortunes. Vance suggests that hillbilly culture fosters social disintegration and economic insecurity in Appalachia. He cites personal experiences: working as a grocery store cashier, Vance saw welfare recipients talking on cell phones, but he could not afford one.[2]

Vance's antipathy toward those who seemed to profit from poor behavior while he struggled is presented as a rationale for Appalachia's political swing from voting Democratic to a strong Republican affiliation. Vance tells stories highlighting the lack of work ethic of the local people, including the story of a man who quit his job after expressing dislike over his work hours, as well as a co-worker with a pregnant girlfriend who would skip work unexcused.[2]

Publication

[edit]In July 2016, Hillbilly Elegy was popularized by an interview with Vance in The American Conservative.[3] The volume of requests briefly disabled the website. Halfway through August, The New York Times wrote that the title had remained in the top ten Amazon bestsellers since the interview's publication.[2]

The publisher is a subsidiary of News Corp.

Vance has credited his Yale contract law professor Amy Chua as the "authorial godmother" of the book, as she persuaded him to write the memoir.[4]

Reactions

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]The book reached the top of The New York Times best seller list in August 2016[5] and January 2017.[6]

American Conservative contributor and blogger Rod Dreher expressed admiration for Hillbilly Elegy, saying that Vance "draws conclusions... that may be hard for some people to take. But Vance has earned the right to make those judgments. This was his life. He speaks with authority that has been extremely hard won."[7] The following month, Dreher posted about his theories about why liberals loved the book.[8] New York Post columnist and editor of Commentary John Podhoretz described the book as among the year's most provocative.[9]

The book was positively received by conservatives such as National Review columnist Mona Charen[10] and National Review editor and Slate columnist Reihan Salam.[11] By contrast, other journalists criticized Vance for generalizing too much from his personal upbringing in suburban Ohio.[12][13][14][15] Jared Yates Sexton of Salon criticized Vance for his "damaging rhetoric" and for endorsing policies used to "gut the poor". He argues that Vance "totally discounts the role racism played in the white working class's opposition to President Obama."[16] Sarah Jones of The New Republic mocked Vance as "the false prophet of Blue America," dismissing him as "a flawed guide to this world" and the book as little more than "a list of myths about welfare queens repackaged as a primer on the white working class."[13]

Historian Bob Hutton wrote in Jacobin that Vance's argument relied on circular logic and eugenics, ignored existing scholarship on Appalachian poverty, and was "primarily a work of self-congratulation."[12] Sarah Smarsh with The Guardian noted that "most downtrodden whites are not conservative male Protestants from Appalachia" and called into question Vance's generalizations about the white working class from his personal upbringing.[14]

The New York Times wrote that Vance's confrontation of a social taboo was admirable, regardless of whether the reader agreed with his conclusions. The newspaper wrote that Vance's subject is despair, and his argument was more generous in that it blames fatalism and learned helplessness rather than indolence.[2]

A 2017 Brookings Institution report noted that "J. D. Vance's Hillbilly Elegy became a national bestseller for its raw, emotional portrait of growing up in and eventually out of a poor rural community riddled by drug addiction and instability." Vance's account anecdotally confirmed the report's conclusion that family stability is essential to upward mobility.[17]

The book provoked a response in the form of an anthology, Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy, edited by Anthony Harkins and Meredith McCarroll. The essays in the volume criticize Vance for making broad generalizations and reproducing myths about poverty.[15]

In an interview with Süddeutsche Zeitung in July 2023, German chancellor Olaf Scholz called the book "a very touching personal story of how a young man with poor starting conditions makes his way." Scholz said the book had moved him to tears, but that he found the positions Vance later took to be "tragic."[18]

Relationship to Donald Trump

[edit]A key reason for Hillbilly Elegy's widespread popularity following its publication in 2016 was its role in explaining Donald Trump's rise to the top of the Republican Party.[19] In particular, it purported to explain why white, working-class voters became attracted to Trump as a political leader.[20] Vance himself offered commentary on how his book provides perspective on why a voter from the "hillbilly" demographic would support Trump.[21]

Although he does not mention Trump in the book, Vance openly criticized the now-former president while discussing his memoir in interviews following its release.[22] Vance walked these comments back when he joined the 2022 U.S. Senate race in Ohio, and later openly endorsed Trump.[23][24] In July 2024, Vance was picked by Trump to be his running mate on the Republican ticket for the 2024 U.S. presidential election.[25]

Renewed attention

[edit]In July 2024, a widely shared post on social media site Twitter falsely claimed that a passage in Hillbilly Elegy described Vance having sexual intercourse with a rubber glove secured between cushions on a couch.[26][27] The posting of the joke came only hours after Vance had been announced as Trump's running mate for the 2024 American general election. The post read "can’t say for sure but he might be the first vp pick to have admitted in a ny times bestseller to fucking an inside-out latex glove shoved between two couch cushions (vance, hillbilly elegy, pp. 179-181).” with the fake citation apparently giving the comment credibility. The joke led to more jokes and a series of memes which proliferated at Vance's expense. The jokes and memes also found their way into more relevant criticism of Vance over his political positions related to women and sex. The flurry of controversies following his announcement as Trump's running mate led to speculation that he might be replaced.[28] Jokes and memes based on the couch intercourse joke are shared both by those who believe them to be true and by people who found it amusing to play into the joke but understand that it does not have a factual basis, it can be hard to differentiate between the two. Experts cited a lack of content moderation on social media as one expanation for why the misinformation had gone so viral.[29]

The Associated Press released a fact check titled "No, JD Vance did not have sex with a couch" on July 24,[30] but later retracted it on July 25, as AP fact checks are only supposed to be of serious claims, not jokes on social media.[27] The account @rickrudescalves was the first one to share the claim, with the author later claiming to have made the joke up themselves. The author believes that the claim was taken by many as believable because Vance has a “couch-fucker” vibe. The author claimed that he had never intended the piece as misinformation, and believed that the most signficant aspect of the whole thing was its exposure of voter naivety and gullibility.[31] At a rally in Pennsylvania, when discussing upcoming vice presidential debate, Tim Walz joked that “I can’t wait to debate the guy... if he’s willing to get off the couch.”[32] Political opponents of Vance's, including Walz, made light of the joke on the campaign trail. This brought criticism, as many of those same people had objected to unfounded and untrue claims being bandied about in the political campaign.[33]

After Vance was announced as Trump's running mate in 2024, sales of the book and viewership for the film on Netflix increased dramatically.[34] In July 2024, the book was censored in China on WeChat.[35]

Sequel

[edit]In 2017, Vance signed a $8m deal to write a sequel to Hillbilly Elegy.[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kuo, Christopher (July 16, 2024). "What to Know About 'Hillbilly Elegy,' Film Based on JD Vance's Memoir". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Senior, Jennifer (August 10, 2016). "Review: In 'Hillbilly Elegy,' a Tough Love Analysis of the Poor Who Back Trump". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- ^ Dreher, Rod (July 22, 2016). "Trump: Tribune Of Poor White People". The American Conservative. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Heller, Karen (February 6, 2017). "'Hillbilly Elegy' made J.D. Vance the voice of the Rust Belt. But does he want that job?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ Barro, Josh (August 22, 2016). "The new memoir 'Hillbilly Elegy' highlights the core social-policy question of our time". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ "Combined Print & E-Book Nonfiction Books – Best Sellers – January 22, 2017". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 27, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ Dreher, Rod (July 11, 2016). "Hillbilly America: Do White Lives Matter?". The American Conservative. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ Dreher, Rod (August 5, 2016). "Why Liberals Love 'Hillbilly Elegy'". The American Conservative. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ Podhoretz, John (October 16, 2016). "The Truly Forgotten Republican Voter". Commentary. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ "Hillbilly Elegy: J.D. Vance's New Book Reveals Much about Trump & America". National Review. July 28, 2016. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ Salan, Reihan [@Reihan] (April 30, 2016). "Very excited for @JDVance1. HILLBILLY ELEGY is excellent, and it'll be published in late June" (Tweet). Archived from the original on April 17, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b "Hillbilly Elitism". Jacobin. Archived from the original on May 7, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ a b Jones, Sarah (November 17, 2016). "J.D. Vance, the False Prophet of Blue America". The New Republic. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ a b Smarsh, Sarah (October 13, 2016). "Dangerous idiots: how the liberal media elite failed working-class Americans". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ a b Garner, Dwight (February 25, 2019). "'Hillbilly Elegy' Had Strong Opinions About Appalachians. Now, Appalachians Return the Favor". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Jared Yates Sexton (March 11, 2017). "Hillbilly sellout: The politics of J. D. Vance's 'Hillbilly Elegy' are already being used to gut the working poor". Salon. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ Krause, Eleanor; Reeves, Richard V. (September 2017). "Rural Dreams: Upward Mobility in America's Countryside" (PDF). Brookings Institution. pp. 12–13. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2020.

- ^ "Germany's Scholz found book written by Trump's VP pick 'touching'". Yahoo News. July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ McClurg, Jocelyn (August 17, 2016). "Best-selling 'Hillbilly Elegy' helps explain Trump's appeal". USA Today. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "The Lives of Poor White People". The New Yorker. September 12, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "J.D. Vance on 'Hillbilly Elegy' and Translating for Trump Supporters". Vogue. February 8, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "'Hillbilly Elegy' Recalls A Childhood Where Poverty Was 'The Family Tradition'". NPR. August 17, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Gabriel, Trip (August 8, 2021). "J.D. Vance Converted to Trumpism. Will Ohio Republicans Buy It?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ van Zuylen-Wood, Simon (January 4, 2022). "The radicalization of J.D. Vance". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Steinhauser, Paul; Gillespie, Brandon (July 15, 2024). "Trump announces Ohio Sen JD Vance as his 2024 running mate". Fox News. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ Oremus, Will (July 26, 2024). "False rumors about Vance, Musk's X show misinfo cuts both ways". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Sato, Mia (July 25, 2024). "The Associated Press removes a fact-check claiming JD Vance has not had sex with a couch". The Verge. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ^ Greve, Joan E. "Sofa so bad for JD Vance as Trump's VP pick faces swirling speculation". theguardian.com. The Guardian. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Joffe-Block, Jude. "What the JD Vance couch jokes say about social media this election season". npr.org. NPR. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Goldin, Melissa (July 24, 2024). "No, JD Vance did not have sex with a couch". Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 24, 2024. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Moye, David. "Person Behind JD Vance Couch Sex Meme Comes Clean". huffpost.com. Huffington Post. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Bedigan, Mike. "Tim Walz lands a zinger on Vance about that couch story - and attacks him for using Hillbilly Elegy to trash his own community". independent.co.uk. The Independent. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Marquez, Alexandra. "Democrats continue to joke about false JD Vance rumor after years of criticizing Trump for spreading misinformation". nbcnews.com. NBC. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Aguirre, Kimberley (July 17, 2024). "J.D. Vance's 'Hillbilly Elegy' streams skyrocket by 1,180%; book tops Amazon bestsellers list, sees spike in library borrows". LA Times. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ^ "Summer Olympics underway, food security scandals set off public outcry, jailed human rights lawyer mistreated (July 2024)". Freedom House. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ Siegel, Tatiana. "JD Vance Quietly Scored an $8 Million Deal for 'Hillbilly Elegy' Follow-Up as Hollywood Straddles Both Sides of Political Divide (EXCLUSIVE)". variety.com. Variety. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- William Allan Kritsonis, PhD – Founding Editor-in-Chief, National Forum Journals (Since 1982), Houston, TX